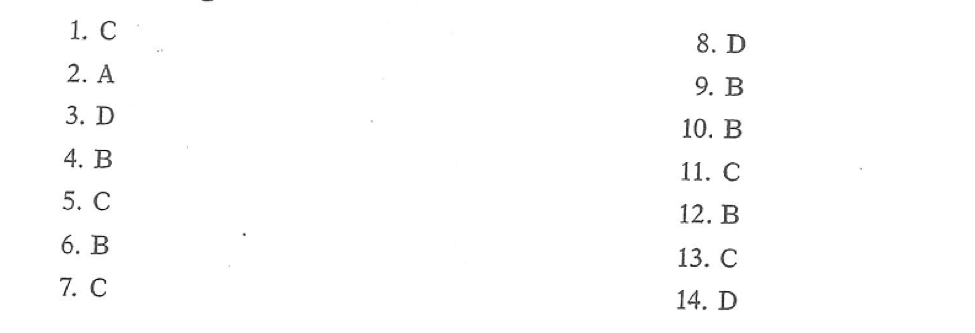

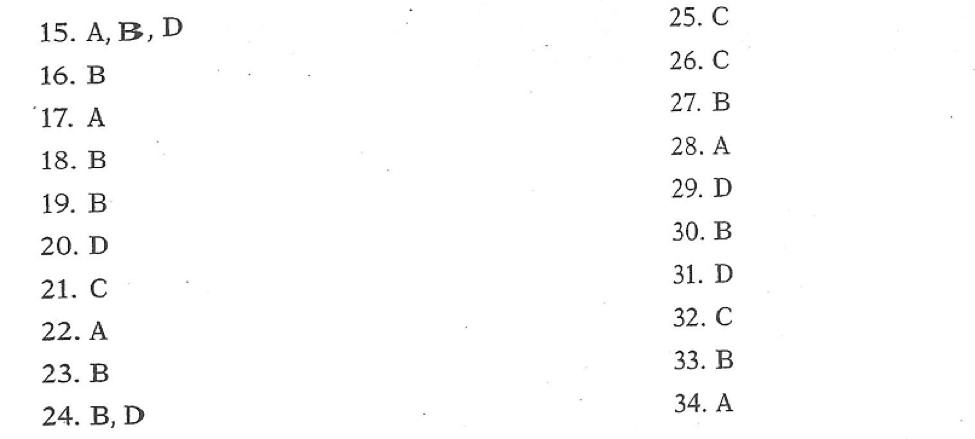

TOEFL IBT Listening Practice Test 31 from Official TOEFL iBT Test with Audio Volume 1 Solution

——————————————————————————-

TOEFL IBT Listening Practice Test 31 from Official TOEFL iBT Test with Audio Volume 1 Solution Transcripts

TRACK 86 TRANSCRIPT

Narrator

Listen to a conversation between a student and an admissions officer at City College.

Student

Hi. Can I ask you a few questions about starting classes during your summer session?

Admissions officer

Sure. Ask away! It starts next week, you know.

Student

Yeah, and I want to get some required courses out of the way so I can … maybe I can graduate one term earlier and get out into the job market sooner.

Admissions officer

That sounds like a good idea. Let me pull up the summer school database on my computer here…

Student

OK.

Admissions officer

OK, there it is. What’s your student ID number?

Student

Oh, well, the thing is … I’m not actually admitted here. I’ll be starting school upstate at Hooper University in the fall. But I’m down here for the summer, staying with my grandparents, ’cause I have a summer job near here.

Admissions officer

Oh, I see, well…

Student

So I’m outta luck?

Admissions officer

Well, you would be if you were starting anywhere but Hooper. But City College has a sort of special relationship with Hooper… a full exchange agreement… so our students can take classes at Hooper and vice versa. So if you can show me proof um, your admissions letter from Hooper, then I can get you into our system here and give you an ID number.

Student

Oh, cool. So … um … I wanna take a math course and a science course—preferably biology. And I was also hoping to get my English composition course out of the way, too.

Admissions officer

Well all three of those courses are offered in the summer, but you’ve gotta understand that summer courses are condensed—you meet longer hours and all the assignments are doubled up because … it’s the same amount of information presented and tested as in a regular term, but it’s only six weeks long. Two courses are considered full time in summer term. Even if you weren’t working, I couldn’t let you register for more than that.

Student

Yeah, I was half expecting that. What about the schedule? Are classes only offered during the day?

Admissions officer

Well, during the week, we have some classes in the daytime and some at night, and on the weekends, we have some classes all day Saturday or all day Sunday for the six weeks.

Student

My job is pretty flexible, so one on a weekday and one on a weekend shouldn’t be any problem. OK, so after I bring you my admissions letter, how do I sign up for the classes?

Admissions officer

Well, as soon as your student ID number is assigned and your information is in our admissions system, you can register by phone almost immediately.

Student

What about financial aid? Is it possible to get it for the summer?

Admissions officer

Sorry, but that’s something you would’ve had to work out long before now. But the good news is that the tuition for our courses is about half of what you’re going to be paying at Hooper.

Student

Oh, well that helps! Thank you so much for answering all my questions. I’ll be back tomorrow with my letter.

Admissions officer

I won’t be here then, but do you see that lady sitting at that desk over there? That’s Ms. Brinker. I’ll leave her a note about what we discussed, and she’ll get you started.

Student

Cool.

——————————————————————————-

TRACK 88 TRANSCRIPT

Narrator

Listen to part of a lecture in a world history class.

Professor

In any introductory course, I think it’s always a good idea to step back and ask ourselves “What are we studying in this class, and why are we studying it?”

So, for example, when you looked at the title of this course in the catalog “Introduction to World History”—what did you think you were getting into .. . what made you sign up for it—besides filling the social-science requirement?

Anyone…?

Male student

Well . . . just the—the history—of everything . . . you know, starting at the beginning .. . with … I guess, the Greeks and Romans … the Middle Ages, the Renaissance . .. you know, that kinda stuff… like what we did in high school.

Professor

OK … Now, what you’re describing is one approach to world history.

In fact, there are several approaches—basic “models” or “conceptual frameworks” of what we study when we “do” history. And what you studied in high school—what I call the “Western-Heritage Model,” this used to be the most common approach in U.S. high schools and colleges … in fact, it’s the model I learned w.th, when I was growing up back—oh, about a hundred years ago …

Uh … at Middletown High School, up in Maine … I guess it made sense to my teachers back then—since, well, the history of western Europe was the cultural heritage of everyone in my class … and this remained the dominant approach in most U.S. schools till … oh, maybe … 30, 40 years ago … But it doesn’t take more than a quick look around campus—even just this classroom today—to see that the student body in the U.S. is much more diverse than my little class in Middletown High .. . and this Western-Heritage Model was eventually replaced by—or sometimes combined Wjth_one or more of the newer approaches … and I wanna take a minute to describe these to you today, so you can see where this course fits in.

OK … so … up until the mid-twentieth century, the basic purpose of most world- history courses was to learn about a set of values … institutions … ideas … which were considered the “heritage” of the people of Europe—things like … democracy … legal systems … types of social organization … artistic achievements …

Now as I said, this model gives us a rather limited view of history. So, in the 1960s and 70s it was combined with-or replaced by-what I call the “Different-Cultures Model.” The ’60s were a period in which people were demanding more relevance in the curriculum, and there was criticism of the European focus that you were likely to find in all the academic disciplines. For the most part, the Different-Cultures Model didn’t challenge the basic assumptions of the Western-Heritage Model. What it did was insist on representing other civilizations and cultural categories, in addition to those of western Europe …

In other words, the heritage of all people: not just what goes back to the Greeks and Romans, but also the origins of African . .. Asian … Native American civilizations. Though more inclusive, it’s still, basically, a “heritage model” … which brings us to a third approach, what I call the “Patterns-of-Change Model.”

Like the Different-Cultures Model, this model presents a wide cultural perspective. But, with this model, we’re no longer limited by notions of fixed cultural or geographical boundaries. So, then, studying world history is not so much a question of how a particular nation or ethnic group developed, but rather it’s a look at common themes—conflicts … trends—that cut across modern-day borders of nations or ethnic groups. In my opinion, this is the best way of studying history, to better understand current-day trends and conflicts.

For example, let’s take the study of the Islamic world. Well, when I first learned about Islamic civilization, it was from the perspective of Europeans. Now, with the Patterns-of-Change Model, we’re looking at the past through a wider lens. So we would be more interested, say, in how interactions with Islamic civilization—the religion … art… literature—affected cultures in Africa … India … Spain … and so on.

Or… let’s take another example. Instead of looking at each cultural group as having a separate, linear development from some ancient origin, in this course we’ll be looking for the common themes that go beyond cultural or regional distinctions. So . . . instead of studying … a particular succession of British kings … or a dynasty of Chinese emperors … in this course, we’ll be looking at the broader concepts of monarchy, imperialism … and political transformation.